Turkey’s Macro Quandary: Politics Meets the Trilemmas

Date:15May2018

We’ve been absent for a while again, so let us make a return by offering a simple narrative that may help to understand Turkey’s current economic troubles and lira’s constant negative decoupling — acknowledging that not much of this will be all that new to seasoned Turkey watchers.

Let’s start by rewinding the tape for about 15 years. It all started kind of nicely then, with the first AKP administration pragmatically focusing on the right stuff, sticking to the EU/IMF anchors, adopting a relatively rule-based policy environment, and so on. But then, things began to change dramatically – the party started having a little too much power even for its own good, checks and balances and the like have weakened sharply, with the institutional environment deteriorating at an accelerating pace, a dynamic that has arguably started sometime around 2007, right before the onset of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

The GFC first had a hellish impact on the economy. The output shrank by some 15% in the first quarter of the ensuing year, and 5% for the year as a whole, as every analyst at the time, including yours truly, spoke of the inevitability of an IMF program in order to get Turkey out of its ditch… Well, we couldn’t be more wrong: the GFC in some awkward way turned out to be the boon that Turkey (and most EMs) has been wanting, with the repeated QE cycles giving, de facto, all EMs something even better than an IMF program: ample financing at low rates with no strings attached for an extended period of time.

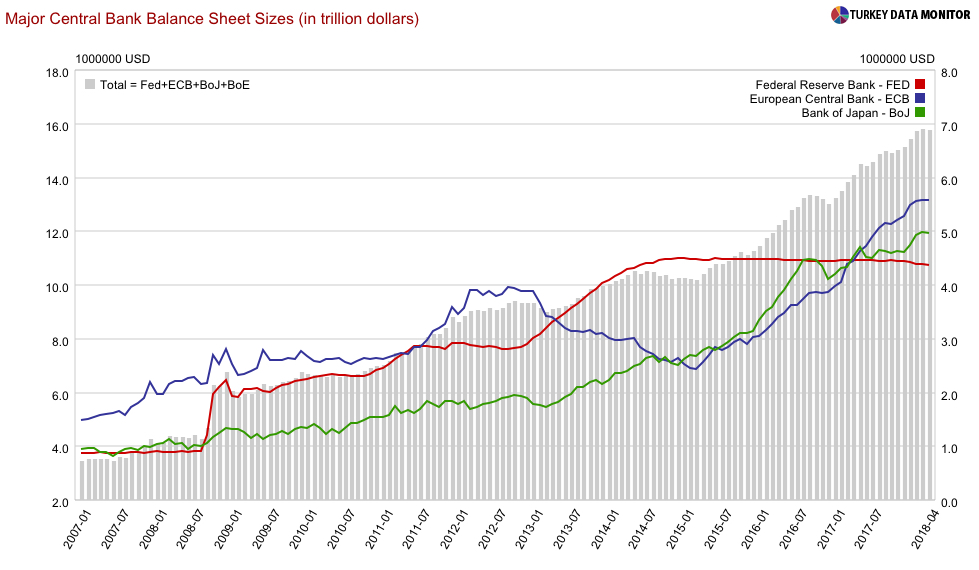

And we all know what happened next — zero rates and some $12-$13 trillion balance sheet expansion from the world’s top 4 advanced county central banks (see chart) led to massive inflows to EMs feeding domestic lending booms. This lending spree went on and on – for about a decade. Every time we thought it may (finally) be over, it actually wasn’t –rates stayed low, new players were pulled into the party (ECB, Japan) when others were planning an exit of sorts (Fed), which, incidentally, has been executed ever more gradually. Needless to say, Turkey benefited immensely from this environment of ample liquidity – as the credit kept flowing and the economy, largely thanks to a construction boom (see Annex I here), growing at stellar rates. In the process, Turkey’s private sector debt grew fastest in the EM space, just behind China.

But now, with the end of ultra-easy money having finally arrived, things seem to be changing – for the worse, of course. Turkey is negatively decoupling, as it has come to be seen by the investor community as one of the most vulnerable and fragile of the bunch. (Here and here are just two recent examples). Ankara, on the other hand, has yet to catch up with the new reality, as it wakes itself up from the exceptionally benign experience — and the resulting hubris — of the past 15 years.

This is where the “two Trilemmas” come handy in putting things in perspective, understanding (sort of) what the root cause of the problem is and also, why a happy ending of sorts to the current Turkish macro quandary may not be all that easy to concoct. One of these Trilemmas, the Monetary Trilemma, is a very old and familiar one, especially to the students of international economics – this is the idea that when money flows freely across borders (or when the capital account is open, in short), it is not possible to simultaneously control the interest rate and the exchange rate – for too long, at least. Ultimately, one of the three has to give. (Here is a quick background and here is NYT column where it is applied.)

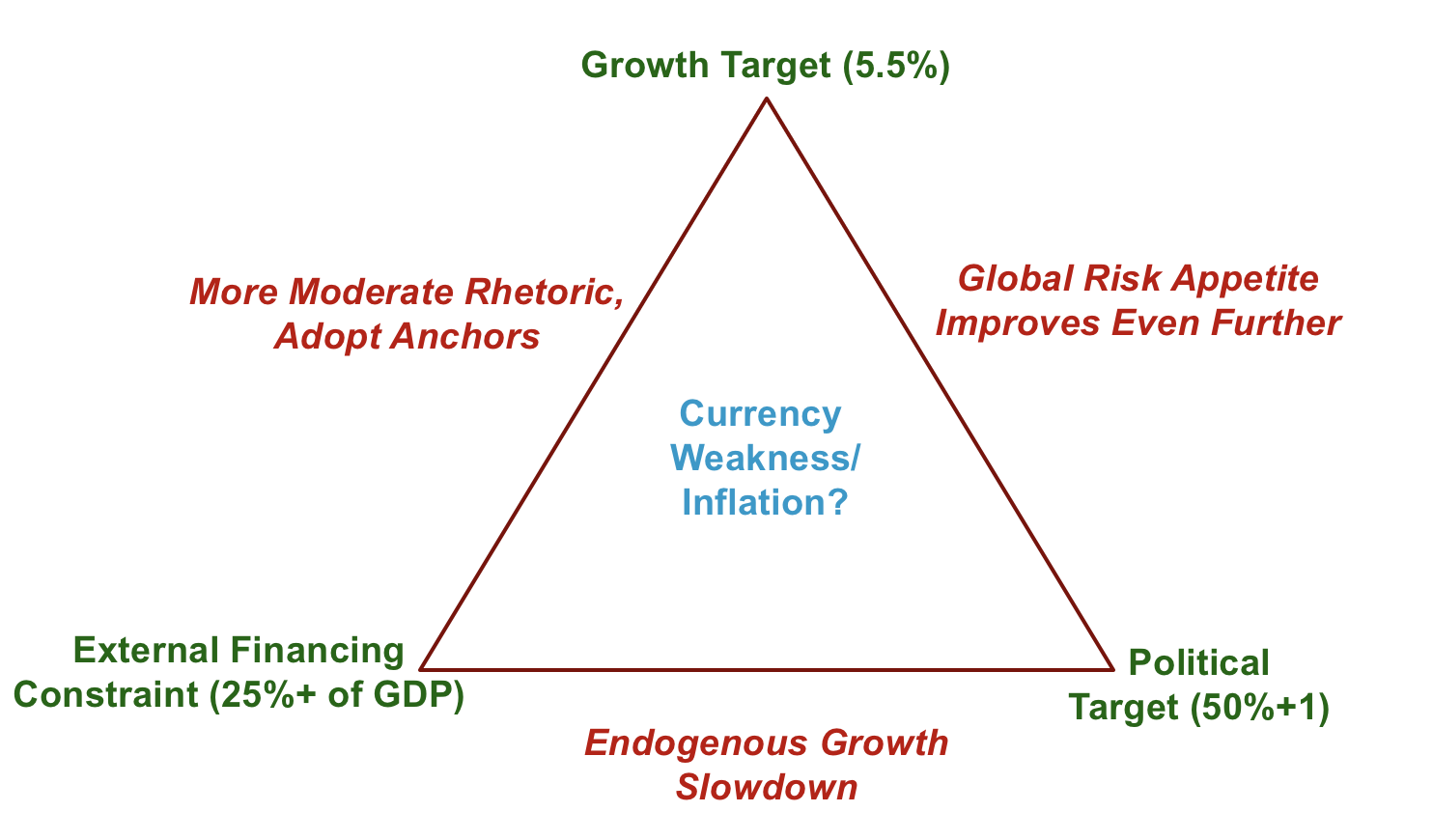

The other Trilemma is Turkey-specific — that yours truly has come up with – it is the idea that: 1) very high and ambitious growth targets, 2) a very high external financing requirement (running at over 25% of GDP comprising a current account deficit at around $50 billon and ST debt of some $190 billion to roll over) and 3) Ankara’s highly unorthodox and combative political-cum-policy orientation are simply incompatible with each other (see chart). Something has to give there as well, i.e. either the politics has to improve (ideally yet very improbably) going back to so-called “factory settings” of 2002-06 or the global environment has to turn super-accommodative again (also not so likely) – or growth has to slow sharply (quite likely).

The two Trilemmas are intertwined, if you will, so that solving the Turkish Trilemma requires working around the Monetary Trilemma. And this is exactly what Ankara is grappling with nowadays, as most recently attested to President Erdogan’s remarks during a Bloomberg interview. True, Turkey has already been dealing with these Trilemmas for some time and going around them kind of successfully. Last year, for instance, the government has managed to engineer an impressive growth rate of over 7%, atop average growth of some 6% since the GFC. But that’s exactly our point – that this dynamic is now finally running out of steam. As noted, most growth in recent years was construction and debt-fueled, and hence hard to replicate, while last year’s growth was largely one-off — a result of massive stimulus measures that cannot be repeated, simply because the financial sector does not have the means for it.

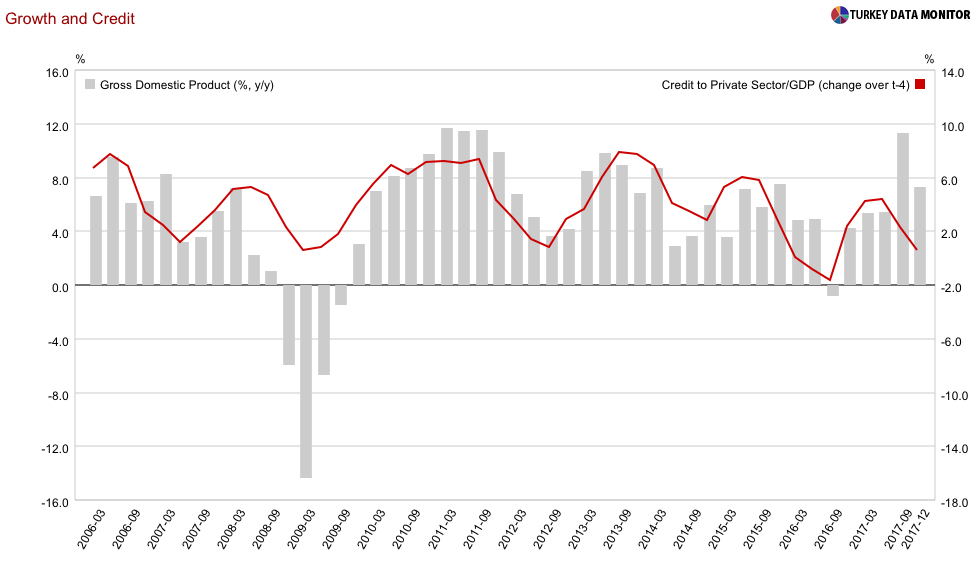

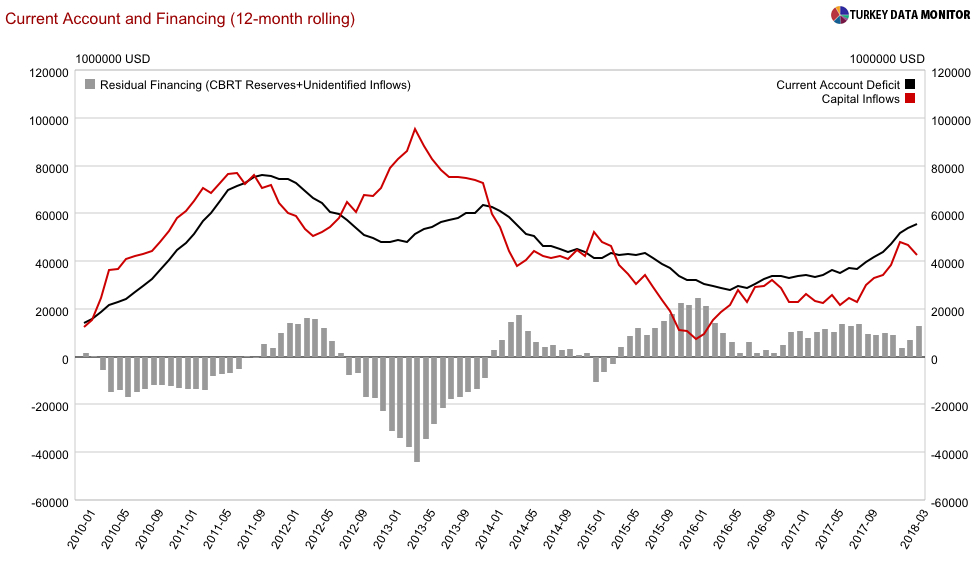

Now addicted to growth and debt, which are anyway rather closely correlated (see chart) – and yet the last big bullets having been fired last year — the government is scrambling for new stimulus measures to keep growth going at its historic and entirely unsustainable pace, but is having very limited success, making the lira suffer in the process. Put differently, the government wants growth at any cost, and for that, it wants to keep interest rates as low as possible. But that cannot happen, unless enough money flows Turkey’s way, which is no longer the case. If anything, we are in the exact opposite situation, having often to count on CBRT reserves and “unidentified inflows” (aka errors and omissions) to make the BOP math add up (see second chart). Unsurprisingly, the lira (and indirectly inflation) emerges as the main casualty of this tension, even though from a “fundamental” valuation perspective, lira is considered to be at “fair value” — most recently by the IMF, according to its very comprehensive EBA assessment (see Box 1 here).

So, what’s the way out? The answer should sort of follow from this discussion — that in order to avoid accidents and things getting even uglier, some “rational” choices will have to be made around the two Trilemmas (or semi-laws of nature), instead of constantly defying them. One particularly investor-friendly option would be to adopt a more orthodox political-cum-policy course (pro-Western, less polarizing, more conventional, etc.) and return to full-fledged Inflation Targeting, doggedly focusing on taking inflation down to low single digits from its new double-digit plateau. With elections in less than two months ahead, this may not at all be feasible now, but it will have to be at some point by choice or by force, given that the current situation is anything but sustainable.